Alfred Tomatis, Mozart, and the Electronic Ear

Thanks to Alfred Tomatis's revolutionary understanding of sound, thousands of lives have been transformed around the world.

In Lake Oswego, Oregon, a little boy is lying prone on a cheerful rug while playing quietly with toys splayed out around him. Oblivious to the earphones piping Mozart into his brain, the child’s tranquility is remarkable for a four-year-old suffering from severe autism.

Prior to his first 30-hour session with the earphones, his grandmother was unable to take him out in public—even to the grocery store—due to incessant screaming. Now he calmly follows her from aisle to aisle. “The change is astounding,” she marvels.

A childhood marked by academic failure was finally behind him, but the disparaging voices of his mother and teachers still echoed in his head. “You’re stupid and lazy,” they had told him over and over, and now he firmly believed them. His future stretched out before him, murky and dank, limited in possibilities.

And then a chance meeting with an eccentric French doctor changed everything.

Madaule went to this man’s clinic and began to undergo an unusual therapy that involved listening to music through a headset. As he did so, the light in his brain finally switched on.

Today he is a successful college graduate, scientist, and author as well as the founder of the Listening Centre, which draws patients from around the world to its clinics in Toronto and Montreal, Canada.

In the south of France, the young abbot was frantic.

Newly appointed as head of a Benedictine monastery in France, he could not understand what was happening to the monks in his charge. Listless and depressed, they were requiring more and more sleep, while their weakened immune systems overwhelmed them with assorted illnesses.

A bevy of medical specialists examined them, but the prescribed medicines and changes in diet did nothing to cure their malady. Finally, a specialist from Paris was invited to investigate.

He immediately ordered the abbot to reinstate the monks’ prior regimen: chanting eight hours a day. (The young abbot had abolished the practice in an effort to modernize the monastery and make it more efficient.) Within weeks, the monks had regained their health and energy and reestablished their normal schedule of intense labor balanced by small amounts of food and sleep.

Who was this Frenchman, and how could mere “sound” transform the lives of so many people?

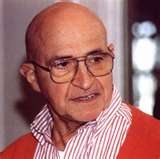

Alfred Tomatis, born in France in 1920, was the son of an opera singer. Immersed in the world of music, he focused his study of medicine on problems of the ear, nose and throat. His first patients, not surprisingly, were opera singers whose hearing and voices were failing them.

Tomatis discovered that the singers’ misuse of their own voices was making them go deaf; in addition, he noted, their voices were unable to produce the sounds they could not hear.

Spurred by the desire to help, Tomatis invented a machine he called the “Electronic Ear,” which alternately amplified high and low frequency sounds.

In effect, the machine exercised the “flabby” muscles of the ear. The singers’ hearing, along with their precious voices, was soon restored.

Tomatis next observed that “hearing” and “listening” differed markedly from each other.

Hearing, he reasoned, was simply the physical ability to passively perceive sound. Listening, however, was an active skill that required the ability to process information by tuning into certain sounds while filtering others out.

If an individual lacked the ability to listen, Tomatis noted, learning was greatly impaired.

While researching this phenomenon, Tomatis observed that people who perceive sounds first through the right ear learn much more easily than those who perceive sounds first through the left ear. This was because the right ear connects directly to the left side of the brain, which is the site that processes language. The left ear, on the other hand, connects to the right side of the brain.

In order to interpret sounds entering the left ear, the brain must first send them through the corpus callosum, which retards the transfer of information and makes it less reliable. In fact, some of the higher frequencies, which are crucial to the brain’s ability to interpret language, disappear altogether.

Tomatis learned that the Electronic Ear could actually rewire the brain, changing it from left or mixed dominance to right dominance.

The results were astonishing.

Not only did speech, concentration and attention improve, but also personal motivation, social interaction, and physical grace.

And the key to this process was music.

In what has now become known as the Mozart Effect, Tomatis discovered that certain types of classical music—especially that of Mozart and Gregorian chants—were particularly effective in rebalancing the brain.

The efficacy of such discoveries can be seen in Paul Madaule, in a little boy who is no longer severely autistic, in a monastery full of healthy and energetic monks, and in thousands of people around the world who have been touched by Alfred Tomatis and the healing power of sound.

For more information about Alfred Tomatis, read The Conscious Ear: My Life of Transformation Through Listening

, a fascinating autobiographical account of Tomatis' life and discoveries.

You can also learn more at his website:

Alfred Tomatis

To learn more about Paul Madaule, read When Listening Comes Alive: A Guide to Effective Learning and Communication

. This book is an inspiring account of how Alfred Tomatis transformed Madaule's life, plus a clear explanation of the principles behind his remarkable transformation.

To learn more about Madaule's clinic, go to:

Listening Centre

Return Home from Alfred Tomatis